Symptoms are not disorders. Disorders give rise to symptoms and require underlying mechanisms to account for them. Does being oppositional and defiant mean you have 'Oppositional Defiant Disorder' if such a 'disorder' does exist? Putting the word disorder after a symptom does not give substance to the existence of a real disorder - it is just a label. The problem is that once a 'disorder' is proclaimed and given 'credibility' then a pharmaceutical cocktail (often experimental and without a substantial evidence-base) will be thought appropriate to it's treatment.

Frequently symptoms that are assumed to be due to one particular disorder may be symptoms actually produced by a different disorder. Therefore assumptions cannot be made without supporting evidence or pathological mechanisms to account for them. Many clinical disorders share similar symptoms so careful analysis and exploration of differential diagnoses must always be undertaken.

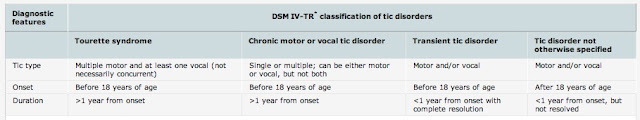

Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and Tourette Syndrome often both share the symptoms of obsessive thinking, ritualised behaviours, sensory hyper-sensitivity, low latent sensory inhibition, poor understanding of intentionality and deception in others, perseveration and poor reciprocity in conversation, reading and writing difficulties, attention deficit and hyperactivity.

There is usually a tendency for physicians to section off certain intrinsic symptoms and designate them as an additional disorder - the so-called splitting approach. For example someone with Tourette Syndrome is very likely to have poor attention and be very active (hyperactive) however they do not require a diagnosis of ADD or ADHD to explain those symptoms. Sensory processing issues are very much an intrinsic part of ASD and TS so a separate diagnosis of Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD) is often redundant. Similarly many that are diagnosed as having ASD or Asperger's and TS together may only have one of these as the symptom overlap is extensive and extremely difficult to breakdown in any clinically/behaviourally meaningful way and is often a result of simplistic/mechanistic thinking or poor understanding of these disorders.

A rational approach would involve the identification of the 'core disorder' and the listing of the symptom/impairment presentation of that individual:

Such as

Tourette Syndrome:

including:

- Motor and vocal tics

- Complex tic behaviours

- Obsessive and compulsive behaviours

- Attention and concentration deficits

- Sensory processing difficulties (with hypersensitivity, visual and hearing difficulties)

Social difficulties:

- Difficulties with conversational reciprocity/perseveration, speech blocking and assessing intentionality, frequent social 'faux pas' behaviours, inappropriate statements etc

Educational difficulties:

- Reading, writing and keyboard skills affected by tics, complex tics, OCB

- Comprehension during lessons and reading are affected by sensory processing and attention difficulties

- Stress due to hiding/supressing tics in the classroom or examination environment

- Disturbance of class due to vocal and overt motor tics

Rather than: Tourette Syndrome, ADD, ASD, SPD, OCD etc

Merely producing a listing of acronyms representing different disorders is often bewildering and unhelpful to the individual or their carers. Some developmental physicians are now tending not to use this approach but to usefully describe the symptom pattern and specific impairments detected, unique to that individual. This avoids generalisations inherent in diagnostic labelling and acknowledges the diversity of neuro-developmental presentations. It is often very presumptuous and clinically inappropriate to cite lists of disorders based on extremely qualitative evaluation. Each 'disorder' opens a large potential perspective of concerns as well as potential, fragmentary and sometimes conflicting and unworkable management approaches. Each individual will have a unique presentation and require a unique approach.